“If the purpose of science fiction is to ask questions about where humanity is going, what is the potential speculative purpose of fantasy?” is a hyper-specific question asked by perhaps no one but me, and yet I am preoccupied by it endlessly. Tolkien had some answers to this, ones that were good enough to codify an entire genre. Among them was what he terms as eucatastrophe, that is: the joy a reader feels when the hero snatches victory from the jaws of defeat. In other words, it’s fine to write a story that exists for the sake of evoking powerful emotions in the intended audience1.

This pulp view of Fantasy—exhilaration without subtext—has been the popular perception of the genre for decades, however Tolkien also believed that “fairy stories” were capable of imparting deeper meaning beyond mere escapism through, let’s call it empathetic verisimilitude. Careful world-building makes a fairy story real, and when the reader can suspend their belief to experience that new, fantastical perspective, they can learn to appreciate things about the real world in a new, fantastical way. Tolkien built his world on the foundations of his personal interests and knowledge base: the Germanic languages, Finnish mythology, Medieval poetry, the moral architecture of his thoroughly studied Catholic faith… this is the historical lens (well, kaleidoscope) through which Middle-earth was first dreamt of. The possibilities of Fantasy are almost endless when every writer is bringing their own unique set of peculiar, obsessive building blocks to the table.

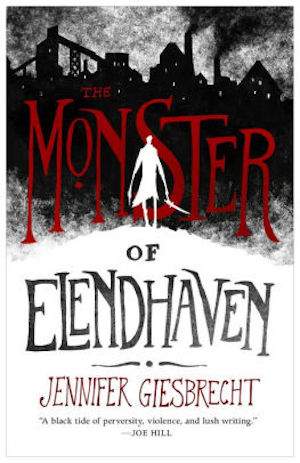

We’re several generations removed from The Lord of the Rings now; Fantasy is a bigger tent with broader goals to match its broader audience. We’ve left eucatastrophe far behind and shed the hyper-strict lines Tolkien drew around secondary world to protect it from the corruption of his dreaded “frame narratives”, but the verisimilitude: ah, that remains. In many ways, Fantasy has become for humanities nerds what hard sci-fi is for physicists and mathematicians: a canvas on which to paint anything from love letters to obscure myths, to meaningful historiographical discourse. Here are five books that use that canvas to particularly vibrant ends:

A Wizard of Earthsea—Ursula K. LeGuin

LeGuin had a deeply articulated philosophy about drawing from the social sciences in her speculative fiction, using anthropology as the basis for her science fiction world-building rather than astrophysics. This allowed her to delve into complex, material questions about subjects usually brushed aside by fiction inspired by the “hard” sciences such as gender, scarcity, and the fundamental organizational structures of society. Her seminal fantasy novel A Wizard of Earthsea—the coming-of-age story of a young boy attempting to escape the shadow of an evil entity—was a conscious reaction against the traditionalist Euro-centric tropes of foundational fantasy, not just drawing on the ontological underpinnings of Taoism to inform the world’s arcane ethics, but setting the book in an Iron Age archipelago far removed from the forests and plains of western Europe. Ged’s journey has the Campbellian trappings of the fantastical bildungsroman, but he is firmly situated in a world inspired by a distinctly modern historiographical understanding of the world, rather than a mythological one. In this sense, A Wizard of Earthsea is the most crucial stepping stone between the folkloric roots of fantasy and the more grounded, naturalistic approach to the genre that has been gaining popularity in the 21st century.

Buy the Book

The Books of Earthsea

A Storm of Swords (and the rest of A Song of Ice and Fire)—George R. R. Martin

So I think we can all admit that it’s not the specific details of GRRM’s world that make it so compelling. I mean, the freaking continents are literally called “West” and “East” and while it’s extremely fun to lose an entire afternoon to the A Song of Ice and Fire Wiki reading about how every single Targaryen who sat on the Iron Throne was an incompetent rube, the world’s background lore isn’t very original either; rather, it’s deliberate hodgepodge of formative western genre fiction from Le Morte d’Arthur all the way Lovecraft. Oh no—the reason Westeros is so enthralling to spend time in is GRRM’s engaging evocation of the medieval worldview. I know we must all be pretty sick of hearing post-moterms on the HBO adaptation by now, but this always struck me as the element of the series most misunderstood by Game of Thrones’ showrunners. The characters in the television show were driven by a distinctly modern political ethic based in individualistic post-Enlightenment values. A good example of this is Robb’s misguided marriage—in the books, a tragedy caused by his clumsy attempts to emulate his father’s strict moral guidelines, in the show, a rote story about “true love” defying political machinations. The concept of “marrying for love” certainly exists within the history and romantic fiction of Westeros, but with the horrific supernatural elements of GRRM’s world hanging over everyone’s heads as a stand-in for the equalizing force of the Danse Macabre, the characters we know and love best have much more “contemporary” devotions: to duty, hierarchy, the family name… this contrast between ASoIaF’s meta-text as a hyper-modern work of deconstruction with its deeply informed diegetic medieval philosophy is what makes it so original and addictive.

Buy the Book

A Storm of Swords

A Memory Called Empire—Arkady Martine

Arkady Martine’s luminous Space Opera follows provincial Ambassador Mahit Dzmare as she is thrust into the political whirlwind of the massive, system-spanning Teixcalaani Empire in a race to unwind the mystery behind the death of her predecessor. Martine is both an accomplished Byzantine scholar and city planner, and she wields her educational and professional backgrounds like a heated knife here. A Memory Called Empire is more than a unique twist on the murder mystery trope—it’s an astonishingly dense vertical slice of an entire Empire forged from a genuinely deep and insightful understanding of Antiquity politics and bolstered by the creative strength to believably translate and transform that reality, and the complicated feelings of those born in proxmity to ancient Empire, to a fantastical setting that becomes simultaneously alien and believable. This book has the best use of pre-chapter epitaphs I’ve ever seen, delving into every aspect of Teixcalaan culture from classical poetry to modern pop culture to infrastructure reports, not a single word wasted. It’s a perfect example of how a historian’s eye can bring endless richness to a fictional setting.

Buy the Book

A Memory Called Empire

The Poppy War—R.F. Kuang

The Poppy War is a lot of things: a coming of age story for its orphaned protagonist Rin, a curiously grim magical school romp, a brutal war drama. It’s also meant to be a rough analogue to the life of Mao Zedong. Kuang drew historical inspiration from her own family’s stories about China’s tumultuous 20th century to craft her startling debut. Direct allegories in spec fiction are a difficult balancing act to pull off, but The Poppy War is never once broad, nor didactic. It flawlessly weaves together its medieval fantasy school setting with a backdrop pulled from the Opium and Sino-Japanese Wars without missing a stitch. She avoids gratuity by using her historical influence to grapple with a very real historical question: what is the psychology of a dictator? Not a “fantasy” dictator—some evil King malingering away in his castle with a divine mandate—but the kind of dictator produced by the world we live in right now, one driven initially by virtues we recognize as inarguably good; one stepped in cultural ideas that are still relevant to us today. This makes The Poppy War something rare and exciting: a true fantasy novel of the current modern era, shining the light of empathetic verisimilitude on a subject difficult to conceptualize when approached factually.

Buy the Book

The Poppy War

Everfair—Nisi Shawl

Everfair is a work of Steampunk-tinged alternative history that imagines a group of socialists and African-American missionaries buying a slice of the Belgium Congo out from under the genocidal grip of King Leopold II. Then it follows the evolution of this new proto-Utopia over the course of nearly three decades, using a “longue durée” narrative device that touches on a broad multiplicity of perspectives at every level of society. In many ways, the novel is more that “meaningful historiographical discourse” I was talking about in the introduction than it is fiction. Understanding the way Steampunk is utilized in this story is like getting a high-speed crash course in how the study of history rapidly changed in the 20th century, from something that was understood on an unspoken level to have a culturally edifying, propagandic purpose, to the multi-faceted, deconstructive school of thought it is today. Steampunk first gained popularity as a highly romanticized view of the Victorian Era, but was quickly co-opted and intelligently deconstructed through the lens of post-colonialism and third-worldism by non-white authors. Everfair goes for the jugular by derailing one of the most horrific tragedies of late colonialism. It’s a beautiful example of how fantasy can reveal just as much about where humanity has been, where we can go, and what we can be as the very best science fiction.

Buy the Book

Everfair

Jennifer Giesbrecht is a native of Halifax, Nova Scotia where she earned an undergraduate degree in History, spent her formative years as a professional street performer, and developed a deep and reverent respect for the ocean. She currently works as a game writer for What Pumpkin Studios. In 2013 she attended the Clarion West Writers Workshop. Her work has appeared in Nightmare Magazine, XIII: ‘Stories of Resurrection’, Apex, and Imaginarium: The Best of Canadian Speculative Fiction. She lives in a quaint, historic neighbourhood with two of her best friends and five cats. The Monster of Elendhaven is her first book.

Jennifer Giesbrecht is a native of Halifax, Nova Scotia where she earned an undergraduate degree in History, spent her formative years as a professional street performer, and developed a deep and reverent respect for the ocean. She currently works as a game writer for What Pumpkin Studios. In 2013 she attended the Clarion West Writers Workshop. Her work has appeared in Nightmare Magazine, XIII: ‘Stories of Resurrection’, Apex, and Imaginarium: The Best of Canadian Speculative Fiction. She lives in a quaint, historic neighbourhood with two of her best friends and five cats. The Monster of Elendhaven is her first book.

[1]Anyway that’s why the Eagles show up at the end of The Lord of the Rings. It’s a eucatastrophe! So we can all stop quibbling about that now.

Guy Gavriel Kay’s works are some of my favorites in this trope, specifically the Sarantine Mosiac books (which take place in a Byzantine-ish society). Lions of Al-Rassan is als in the same world and is modeled on Moorish Spain…his books are always fantastic.

Juliet Marrilier also has some great books that are based on fairy tale/folk lore, but Foxmask/Wolfskin are a really interesting take on Viking/Pictish society.

The fact that you’re admitting to a distinction between science fiction and fantasy but claiming that A Memory Called Empire qualifies as fantasy rather than science fiction baffles me.

Ursula le Guin was the daughter of anthropologists specializing in West Coast Native American tribes. It shows.

Louis McMaster Bujold’s Chalion series is based on her study of medieval Spanish history.

@@@@@ 0: The reason Westeros is so enthralling to spend time in is GRRM’s engaging evocation of the medieval worldview.

For a peek at the medieval world view, check out William Marshal. He’s the closest I know of, in English history, to a real life fairy-tale knight. He started as a knight-errant. He served Henry II, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and the Plantagenet boys faithfully. He ended up the Earl of Pembroke and Regent of England.

We know this because William told his story for some amanuensis to transcribe. The one thing we don’t know is about his time on crusade. His crusade came through his service to the Young King Henry. When Henry knew he was dying, he asked William to fulfill his oath. Go on the crusade Henry had sworn to make. Which William did.

The Marshal never described his adventures in the Holy Land. Why? Because they were not his adventures. They were part of Yong Henry’s story.

I’d also put Cherryh’s Foreigner books in this category. Very deep dive into 200 years of history that drive current events of the novels in the series, just with that special focus on non-human (atevi) history.

I think the question you pose is valid : “If the purpose of science fiction is to ask questions about where humanity is going, what is the potential speculative purpose of fantasy?”

I’ve often thought fantasy delves more in to spirituality and the forces behind the choices human beings make– that there are forces for good and evil influencing players in the course of history and worlds.

There is some merging of the genres– while SciFi focuses on technology, Space Operas for example which have SciFi elements i.e. future technological advances nonetheless have strong fantasy elements and is not strictly SciFi.

May the force be you !

@3 – Yes, I agree – just finished re-reading Always Coming Home and was reminded of how strongly the Kesh and their culture reminded me of the native inhabitants of the West Coast, so much so that I’ve wondered if maybe they were the descendants of First Nations people who survived the collapse of our industrial culture, while the settlers all died off.

And Earthsea really reminded me of the Salish Sea.

I really enjoyed the article!

Tolkien didn’t draw strict lines around anything. Those who read him and wanted copycats did that.

The speculative nature of fantasy covers everything, just set in a different framework so we can see it from another angle. It includes past, present and future. It includes inner worlds and outer. It includes real and unreal settings. It’s simply mainstream fiction with a broader playground.